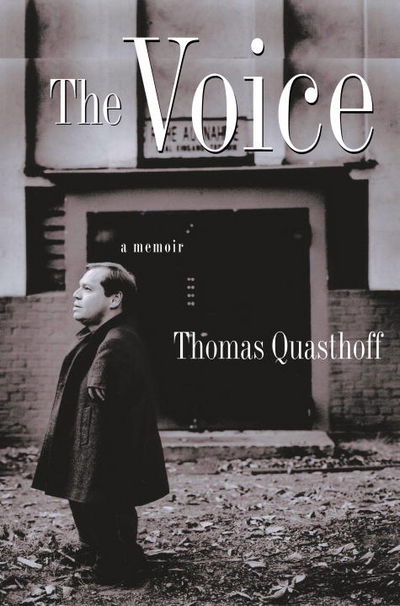

The Voice: A Memoir Hardcover - 2008

by Thomas Quasthoff; Recorded by Michael Quasthoff; Kirsten Stoldt Wittenborn (Translator)

Summary

From the publisher

The Voice is the profoundly inspiring memoir of one of the most sought after and admired classical singers in the world--a man who has arrived at the summit of his artistry by overcoming extraordinarily daunting odds. Thomas Quasthoff, the German bass baritone, stands a shade over four feet tall, his severely underdeveloped arms and hands the result of thalidomide poisoning while he was in his mother's womb. But through stunning determination enlivened by an impish sense of human, Quasthoff has overcome his physical limitations and Dickensian childhood, cultivating his musical genius and thrilling classical music lovers with his sublime voice. What shines through Quasthoff's astonishing story is his staunch refusal to wallow in self-pity, to see himself as a victim. Whether he is evoking a harrowing childhood marked by multiple agonizing surgeries, relating folksy family anecdotes, expressing his devotion to his students as a professor of voice, expounding on his love of jazz and American popular music (he is a great admirer of Stevie Wonder), or unburdening himself of his wickedly outspoken views on art and disability, Quasthoff's unerring sense of humanity, boisterous conviviality, and fierce honesty are always on display. The Voice is utterly winning--a memoir to both marvel at and enjoy.

Details

- Title The Voice: A Memoir

- Author Thomas Quasthoff; Recorded by Michael Quasthoff; Kirsten Stoldt Wittenborn (Translator)

- Binding Hardcover

- Edition First edition

- Pages 241

- Volumes 1

- Language ENG

- Publisher Pantheon Books, New York

- Date 2008

- ISBN 9780375424069 / 0375424067

- Weight 0.86 lbs (0.39 kg)

- Dimensions 8.48 x 5.84 x 1.03 in (21.54 x 14.83 x 2.62 cm)

- Library of Congress subjects Quasthoff, Thomas, Bass-baritones - Germany

- Library of Congress Catalog Number 2007039089

- Dewey Decimal Code B

Excerpt

If You Can Make It There

"Brrroeek," drones the jackhammer. "Brrroeek, brrroeek." When it rests you can hear the radiator grumbling and the baseline murmurof traffic rising up from Columbus Circle to the fifth floor of the Mayflower Hotel. Somewhere police sirens are shrieking. New York is a loud city, even at one o'clock in the morning. Again, "BRRROEEK." Next door a clonk, and now someone's curses. Or did that come from the construction workers below,

the ones who've been racking my nerves for the past three hours? I hope they get paid a nighttime bonus for this nastiness.

I slide off the much-too-soft mattress and turn on the television. Through the news floats John Glenn, eighty years old and still dreaming of space-zap-"the mysterious prostitute murderer of Newark. Seventeen victims since 1994"-zap-a fat man in a green apron pours "rich molasses-based sauce" over a gigantic rack of pork ribs. "Spicy but not spicy enough," according to the fat guy, who then holds up "the best garlic paste in the world"-zap-on the History Channel General Patton chases Rommel's Africa Corps through the Libyan desert. Once again, serves those old Nazis right. In Libya grenades explode, soundlessly now because the jackhammer is at it again, right below my window. "Brrroeek, brrrrrroeek, brrroeek." Shattered, I switch off the box and pace the room.

This is just super. Tomorrow, November 13, 1998, Gustav Mahler's Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Youth's Magic Horn) is on the program at Avery Fisher Hall. It is my long-desired debut with the New York Philharmonic. The baritone parts are high and not entirely simple. I need a clear head and a lot of sleep, but so much for that. All I can do now is seek out a soothing tonic. I call my brother, Michael, who is three rooms down with girlfriend, Renate, and who most definitely cannot sleep either. Thank God, those two are always up for a late beer, and for any other nonsense I propose.

In the hallway outside their door I can already hear Renate. "Sleepless, helpless, sleepless," she sings as her red mane peeks around the door.

I counter with Don Giovanni: " . . . night and day it's toil and sweat for a master hard to please."

"To Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and the German Union Federation, which guarantees the working class its rest," Micha grumbles, cracking open three bottles of beer. The New York construction workers, unimpressed, continue to flatten the earthly realm with their diabolical tools. At the window, we silently drink our beer and gaze out over Central Park, which yawns like a gigantic black hole against the illuminated concrete blocks of midtown Manhattan.

I, too, have to yawn. "What time is it?"

"Just past three," Renate says sympathetically. Micha fetches more beer. He holds the bottle up to the pallid moon and proclaims: "Du bist die Ruh, / der Friede mild, / die Sehnsucht du, / und was sie stillt." ("You are rest / and gentle peace; / you are longing / and what stills it.")

"RŸckert," I say.

"Hit," nods Renate.

"Prost," Micha says, stone faced. One beat later we have to laugh. There is nothing like a solid humanist education. We are a good team.

"Eeeeeeeeeeeeeeeaaaaaaaay." The next morning the jackhammer is still ranting when "Mr. Quasthoff takes his voice for a spin," as the chambermaid calls it, with a charming smile, when she drops off the footstool that allows me to conduct my ablutions. "Eeeeeeeeeeeeaaaaaaaaaay." It might not be lovely to hear, but it does loosen the vocal cords. Despite the trying night I passed, I am content: the voice is in place.

After a leisurely shower I put the footstool in front of the sink, climb up, and grimace at what I see in the mirror.

"Crippled arms and legs, no laughing matter." That's how a tabloid paper once put it, but I see the situation differently. Here is a four-foot three-inch concert singer without knee joints, arms, or upper thighs, with only four fingers on the right hand and three on the left. He has a receding hairline, a blond pig head, and a few too many pounds around his hips, and he is in a superb mood. All he needs now is a shave.

Half an hour later we sit down for breakfast at the Carnegie Deli, corner of Seventh Avenue and Fifty-fifth Street. It's part of New York legend--because it appears in at least two Woody Allen movies, because it serves the best kosher pastrami sandwich in the city, and because of the linen napkins the manager hands out to his regulars, like Kinky Friedman and his buddy Ratso, while the other customers make do with paper (according to Kinky, who includes this detail at least once in each of his crime novels).

Needless to say, our napkins are paper. "It's all BS. Everybody gets paper napkins here," my brother mumbles through a mouthful of pastrami.

Renate checks her watch. "Guess it's still a little early for the boldfaced names."

"I bet you not," Micha says, pointing towards the bar with his fork. The genteel older lady who has just sashayed in may not be Kinky Friedman, but she is sporting a hat whose size and shape would make any Texan green with envy. It is purple, to match her dress. As she makes her way towards us, we see that her right hand clutches a pen and her left, a notebook. Her voice sounds

like a rusty bell:

"Oh, you are the fabulous singer! What a pleasure to see you. Please, give me an autograph." I turn violently pink, as if my face is struggling to match her outfit, and then do her the favor. How did she recognize me? She says she has seen my face on CBS, and the New York Times published a praiseful piece by the feared critic Anthony Tommasini. She has tickets for tonight.

"Naturally! We know you in this town, honey," her voice shrills through the place as she leaves our table and teeters back to hers.

Nice, I think, a little kooky, but a nice lady. I don't expect other people to recognize me, but on our way back to the Mayflower, as we cut through Central Park, I have to give another half dozen autographs. They haven't mistaken me for Danny DeVito--they really do want my signature on the shopping lists, newspapers, and ticket stubs they hastily fish out of pockets and purses. Everyone says New Yorkers are rude and tough, but it's amazing how open and friendly these people are. Not to mention crazy about music! Everyone wishes me "good luck" for the concert. I can use it.

I don't usually suffer from stage fright, and appearances in the United States are nothing new for me. I have sung in Washington and Seattle, in Chicago, Portland, and Boston; in Eugene, Oregon, I am a regular guest at the Bach Festival organized by my mentor and friend Helmuth Rilling. But this is my first appearance in New York. The fact that I am staying on the Upper West Side and in a few hours will be standing in one of the most beautiful concert halls of the world--with the New York Philharmonic--it makes my heart race after all. Or is it just the hotel elevator? My

conventionally shaped readers should know: elevators are, for people of my format, indispensable, but when they are crowded (and they usually are crowded) they are also a terrible trial (a blow below the belt, so to speak). To make matters worse, the Mayflower's tourists seem determined to buy up half of the city. I don't believe they care what they carry out of the boutiques of Madison Avenue or Bloomingdale's, Saks, or Macy's; after all, most of that stuff is available in Osaka, Lyon, and DŸsseldorf. What's important is the shopping bags themselves with their fine and, one hopes, recognizable writing, which, back home, will induce envy and indicate restless hip-hunting and international creditworthiness.

About three dozen of these hunters and gatherers are now packing themselves and their purchases into the elevator. A stampede is nothing compared to this; only by resolutely exercising my stentorian voice can I secure a spot. While the cabin slowly rises my spirits sink. The air is thick and warm. Wedged in between purses, boxes, and plastic bags, beset by protruding behinds, trouser legs, and nylon-covered ladies' thighs, before we reach even the second floor I begin to feel like a piece of cheese melting on a grilled sandwich. The five floors I have to travel feel more like fifty.

Once in my room I fall onto my bed and count "seven . . . eight . . . nine . . . out." Technical KO. I take two aspirin and try to chase away misery with the Ross Thomas dime novel Renate brought me from the Village. It starts with the sentence "It began like the end of the world will begin: with the phone ringing at three a.m." "At least it's only noon," I think, some consolation. Then the aspirin takes effect and I drift off into the realm of

dreams, a calm and pleasant place with no telephone. Thus apocalypse is kept at bay and-voilà-after two hours of deep sleep, the worst is over. I feel better. The last bit of nervousness is filed away under "creative tension," and professional routine takes its place.

Performing music is not unlike rock climbing. Before you begin you check your gear super-carefully: Does the tailcoat have to be ironed again? Is the hanky beautifully folded? Would the white turtleneck be better today, or the black one? Are the patent leather shoes shining? Where are the black socks, and where is the bloody comb? Then you review the score mentally, concentrating on the difficult ridges, gorges, and overhanging rocks. Finally, you need a strengthening refreshment. Not exactly "six eggs, sunny side up, with hot cocoa," the kind of thing Anderl Heckmair would put away before fastening his bundle and climbing across the wall of Eigernord. No, something easily digestible that won't turn your stomach into a stone pit encroaching on your diaphragm. For me, a few cookies usually suffice, rinsed down with juice or water.

After the snack comes the most important preparation of all: warming up the voice. I once again jump into a hot shower, for nothing massages the voice better than sultry air full of warm droplets. The vocal stretching lasts a half hour or forty-five minutes, depending on the repertoire. For higher parts, like Mahler's Wunderhorn Lieder, it takes a little bit longer.

At four o'clock sharp Micha comes to help me don my professional attire. Though not absolutely necessary--I can usually manage by myself--it simplifies the procedure. Unlike me, he is able to crouch with ease to peer beneath the tables, cabinets, and dressers that combs, shoehorns, and socks have a way of retreating to just before a concert. You know the axiom--"Things disappear when you need them most." What treacherous law of life is behind this I have never made out, and unfortunately, neither has science. Probably all efforts to solve this problem are quashed by lobbyists of the textile and accessories industries.

"Got one!" My brother is triumphantly waving a sock when Linda Marder calls. Blond, capable, roughly my age, Linda is my New York agent and a truly cool person. Together with her colleague Charles Cumella, she sits in a small office on Ninety-sixth Street and handles all my business between Boston and San Francisco. They take care of good--i.e, artistically interesting-- engagements and, more important, reject the bad ones. They coordinate PR, negotiate contracts, and make sure I am decently compensated. They even find the least taxing flight connections and book convenient hotels for my tours. In short, Linda and Charles make sure that I am okay and that no one takes advantage of me. As one says here, they do a very good job.

Linda reminds me of the New York Philharmonic's request that I make myself available after the concert for the so-called ten-minute smile, a euphemism disguising a uniquely American triathlon. Exercise number one: thirty minutes of hand shaking; exercise number two: forty minutes of small talk; and finally, the dinner obstacle course, complete with asparagus hurdles, a maze of cutlery, and a squadron of boiled lobster. In the United States cultural institutions don't get a single cent from public funds but get by entirely on sponsors, donations, and entrance fees. That means that without the goodwill of private donors, the concert tonight could not take place. So I will show up, cultivate some goodwill, and, I hope, meet some interesting people.

"You will," Linda assures me. "By the way, Avery Fisher Hall has been sold out for weeks."

"Wow." I imagine the hall filled with three thousand people. I have never sung in front of such a mighty assemblage.

"Are you nervous?"

"Not anymore. I am just happy to be able to perform here."

"Very good, Tommy, that's the right attitude!"

Meantime, Micha has dug up the second sock. When the shoehorn reveals itself, I glide into my patent leather slippers and am on my way, even though it's a bit early. Avery Fisher Hall is only fifteen minutes away, and I like walking a bit before a concert. I stroll up Central Park West until the twin towers of the San Remo and El Dorado appear in the distance. Stars like Marilyn Monroe and Groucho Marx used to live at the San Remo, later to be replaced by Diane Keaton and Dustin Hoffman. Shortly after spotting them, I make a left onto Sixty-fourth Street, and the building canyon frames one of the most magnificent temples of secular modernity in the world: Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts.

Every year five million aesthetic pilgrims visit these fifteen acres, home to four theatres and two concert halls that offer up the best of dance, drama, classical music, and jazz. The centerpiece is the Met, the Metropolitan Opera House, which resembles a Bauhaus version of the Athenian Parthenon, its face covered with high arched windows. Next door the New York State Theatre hosts the City Ballet, while the Philharmonic makes its home in Avery Fisher Hall. Who can believe that gangs like Leonard Bernstein's Jets and Sharks ever dominated the neighborhood, and in the middle of the last century? Not two decades later, in May 1959, the gangs were history. Bernstein lifted the conductor's baton, the Juilliard Chorus belted "Hallelujah," and President Eisenhower plunged his shovel into the flattened slum floor. Lincoln Center was born.

At Avery Fisher Hall's stage door, the doorman looks surprised as he nods hello. It's only five, and I am early--as usual. "You are always and everywhere too early," my brother would tease me if he were here. "Too early for trains, too early at the airport, too early for dinner reservations. If you go on like the devil, friend Hein will send you to the grave way before your time as punishment." For me, "being there at the right time" is the only effective strategy for coping with the inscrutability of life. Lateness and dawdling are suspect to me. Besides, I hate rushing about unnecessarily. My brother, on the other hand, is your typical lastminute man, a jolly solipsist who believes that all the world has nothing better to do than wait for him. As you might imagine, when the two of us travel together, sparks fly. I sit and seethe, insisting that the time to depart has passed and angrily kicking whatever I can, as Micha calmly lights another cigarette, peruses the SŸddeutsche, and calls me a hectic neurotic. It's quite a drama.

For the past two days I have been working on a different twoman sketch, this one with a stagehand called Jim. It goes like this:

Jim: "Hi, little big man."

Quasthoff: "Hi, big belly."

Jim: "Everything's okay with Gustav Mahler?"

Quasthoff: "Yes! He rests in peace. I hope the concert doesn't raise him."

Jim's roly-poly belly jiggles like pudding as he laughs at our routine, sending sunny chuckles burbling up to the ceiling. It's fair to say that the acoustics here are brilliant.

On the stage, I inspect my workplace one last time before the concert. Our contract includes a memo that my agency sends to every organizer. "Thomas Quasthoff needs for the concert: a podium, about three by three feet, sixteen to twenty inches high (roughly corresponds to a conductor's podium without rail), with two steps and a chair (if possible with adjustable height), a wooden score console."

These requirements are neither extravagances nor affectations; they are related to my disability. It is exceedingly difficult to stand throughout a longer concert (even my "normal" colleagues can manage passages that last hours only by taking breaks to sit down). And when ecclesiastical or orchestral works are performed, there are always several soloists arrayed alongside the conductor, not unlike a soccer team. Without a podium bringing me up to eye level, the maestro would need the visual field of an owl to get his commands across to the tot surrounded by a forest of high tenors and baroque altos. Similarly, I would be forced constantly to locate the prompter behind the backs of my colleagues. I would sway like a reed, which would not exactly amplify my aesthetic appeal and might even give some viewers the idea that I had had a nip before the concert. This is the math: 20-inch podium + 36-inch chair + 27-inch seated baritone = seeing and being seen. The podium holds the heavy score books for me and makes turning the page much easier; it should be made of wood, a material that, when it comes to podiums, pits itself more reliably against the gravitational forces than metal.

What other condition must obtain if we are to have a successful performance?

The fortitude of all those involved is necessary. Whoever has spent his youth interpreting songs for audiences in school auditoriums and small town halls knows exactly what I mean. Well do I recall the many nights I had to focus on maintaining my balance atop a stack of fruit crates while trying not to wake the cultural official snoring blissfully in the first row. After all, he had been coaxed into attending because we hoped he would throw some subsidies our way. I managed to sing in spite of it all, but don't ask how.

At the Zombie Club in Wennigsen we never even got that far. I was singing with a soul band at the time. Beside me the keyboard player sat atop a precarious plywood platform. Right after the instrumental intro the entire construction collapsed with a bang. We survived, but the electric piano and the amplifier unfortunately did not. The rest of the band tried to save what could be saved, but two numbers later the subwoofer gave up, and the concert was over. And what was our reward? Expenses, jeers, and a bump on the head as big as a potato dumpling. That's the music business.

This is something different, though; that's all in my past. And it's high time Tony Shalit appeared. Sure enough, here is the knock at my dressing room door. In comes a man in his late fifties, elegant yet impish, his face tan, his features sharply chiseled, his icy grey hair sparse above a high forehead. With a nonchalant movement his sunglasses disappear into the breast pocket of his sport coat. Then he beams and throws his arms around my neck and plants a moist kiss on my cheek.

"Hallo, Sweetheart, wee gates?"

"Everything is great."

"Alright, then, you will be good tonight. You will be formidahbel."

"Hmm."

"You will dazzle New York."

"Hmm."

"Don't say 'hmm,' say 'yes!' " Tony is stilting euphorically from wall to wall, looking like a mating marabou. "The best orchestra in the world with the best singer in the world. That will make history."

"Tony, come on."

"I talked about it with Colin Davis. I said to him--"

"Tony, sit down!!!" I would rather not know what he said to Davis. Sir Colin is not only the head of the London Symphony; not only one of the great interpreters of Mozart, Sibelius, and Berlioz; and not only a knight of Her Majesty Elizabeth II. Tonight he is the conductor of the New York Philharmonic. I would be mortified if he decided that Mr. Quasthoff and his herald were suffering from a Napoleon complex. Tony, on the other hand, does not give a damn. From Bayreuth to Sydney he enjoys a solid reputation in the music community as a seasonal eccentric, bon vivant, and free radical. Now he wheezes as he drops into an armchair, ready as always to have the last word.

"I know it will be woonderbah."

"We'll see."

"What do you mean, 'see'? You have to stroke my ears, not my eyes."

That's how it has been with us for years. A decade ago we were both chugging through the Mediterranean on a luxury cruise ship, Tony as a passenger, I in the capacity of "Cultural Diversion" (and in good company, too: also aboard were the violinist Vladimir Spivakov, the god of cello Mstislav Rostropovich, and his wife, the celebrated opera diva Galina Vishnevskaya). It was my first cruise and my first excursion into the world of hundreddollar tips. I found many things bewildering: who knew that one could change one's outfit seven times a day, and what exactly was this nouvelle cuisine, which took pains to stretch into five courses what at our house fits comfortably on one plate? Having to prove myself alongside some of my musical heroes didn't make things any easier, and I paced the deck feeling like an impostor until Tony rescued me. He heard my first concert, declared it "magnificent," and took me under his wing. Tony was the captain's buddy, the stars' buddy, the waiters' buddy--in short, a friend to one and all. He ordered the right wines, made the right conversation, and conducted himself with intelligence and wit all day and all night. How he did it? At first I thought he managed thanks to his curious diet: for breakfast he would have a joint with tea; at lunchtime, a joint with fish; and at night he would supplement his salad with some grass. But this wasn't it. Plenty of our powerful and successful shipmates would have a martini with their coffee, but Tony was something special: a free spirit who cultivated the unconventional--at times veering into the highly comical and even kinky--not for its own sake but because he believed obstinacy, independence, and tolerance to be fundamental human rights. Of course, this position can only be taken by those who can afford it, as Tony can. As an international lawyer he made a fortune by finessing a way for Australian companies to access the American market. At fifty he put work aside and decided to devote himself to family and a few hobbies, above all the obsession of his life: music. So when he is not sailing across the Indian Ocean, buying valuable books and art, or hopping into a helicopter in search of fresh caviar, he is following singers and conductors around the globe like a well-off Deadhead.

Since that cruise we have been fast friends, and whenever he can Tony escorts me on my tours--a guarantee of lots of fun. Something crazy always happens, often occasioned by the seemingly unlikely stimulus of Tony's tendency to embark on exhausting excursions through music history. He'll start with Monteverdi and end by saying, "I just don't know what this Schönberg wanted." In a museum café, fine, but at the butcher's counter of a German supermarket such behavior can raise blood pressure to unimagined heights, especially in the line behind him. Tony is a polished man of the world and archromantic who can be moved to tears by the first notes of the Tannhäuser overture. But he is also from New York, where boys learn in kindergarten never to leave a verbal injury unanswered. And so Tony turns around, makes a face like Robert De Niro in Cape Fear, and barks that "Krauts," having begun and lost two world wars, should know better than to meddle in other people's business. Once that has been clarified he can order, ever so calmly, half a pound of "bloody roast beef" and march to the register, not deigning to dignify his audience with so much as a glance. In a world whose inhabitants increasingly resemble the products of Playmobil, Tony should be protected as an endangered species.

But he has got to get on his way now. A gong resounds from the speaker above the door of my dressing room, indicating that the concert will begin in twenty minutes. I accompany Tony for part of the way so I can watch the entry of the New York audience from the foyer, an instructive spectacle for a native of Old Europe. What strikes me first is the complete absence of that solemn, respectful murmur that has been flowing around German stages since the days of Goethe and Schiller. Instead one enjoys the relaxed atmosphere, the matter-of-fact attitude with which the Americans have--yes, I will put it this way--made use of their cultural temples. One sees humans of all skin colors, all age and income groups, though here it is harder than it is at home to tell the well-to-do from the just-scraping-by. Of course, even here one finds the class-conscious parade of custom-made suits, impressive jewelry, and designer wardrobes, but most visitors wade in jeans and sneakers through the ankle-deep merchandise. Some carry shopping bags, others are gobbling up a last-minute tuna burger, while others still read in comfortable corners perfect

for lounging. Do these masters of the universe study the evening's program bulletin? No, their attention is held by the sports section of the Post, which proclaims today that the Rangers once again lost to Boston. I suppose that "The Sentry's Nightsong" ("I cannot and may not be merry") will most certainly hit a nerve in the auditorium later tonight.

This fundamentally democratic casualness, though it is very likable, has its drawbacks. For example, towards the end of a not-so- compelling performance, half of the audience jumps up and scurries towards the exit, drowning the final bars in a cacophony of rustling clothes, clattering chairs, and querulous maneuvering, even as the conductor urges the orchestra to a stubborn yet helpless forte. No problem, a pizza baker from Seattle once told me, pointing out that he donated five thousand tax-deductible dollars to the opera each year, earning himself not only a spot on the brass plaque in the foyer but also the right to get his car out of the garage before the inevitable traffic jam. I suppose it depends on how you look at it. Personally, I view Homo Americanus's habit of valuing the classical arts no higher than other forms of intelligent entertainment--whether film or basketball--as a true achievement of civilization. It does not harm the quality and professional appreciation of artists; rather, the opposite is true.

Returning to the backstage area, I notice that even the aces of the New York Philharmonic are tense like racehorses before the start. A cloud of scales, shreds of melody, and tangles of chords mingle with the aromas of hair gel, perfume, sweat, and rosin. Musicians are warming up their instruments, loosening their lips and fingers, wandering around or standing together in little groups. The gong sounds for the second time. The countdown is on--only ten minutes left. Last puffs on cigarettes, here a dress adjusted, there a bow tie, kisses exchanged, and, following old theatre custom, colleagues spitting over each other's shoulders.

"See you," a clarinet is calling out to me. Then the orchestra has got to go on stage.

Colin Davis opens the evening with the King Lear overture by Hector Berlioz and Frank Martin's Petite Symphonie Concertante. The Mahler lieder are scheduled for after the break, so I can still sit for a while in my dressing room, do a few voice exercises, and follow the concert via loudspeaker and TV monitor. When the first notes float through the hall I stare at the screen. The sound quality of the transmission is, well, not the best, but one imagines it must sound wonderful in the hall. After a while I want to know for sure and stalk over to the right side entrance of

the stage. Through the narrow opening I see the percussionists, compact men who smash their sticks mightily and precisely onto the skins. I see hairdos and violin bows fly, and I see Sir Colin, calmly bringing the romantically bubbling King Lear prelude to a climax. He is directing a near perfect sound body: fully trained, with highly sensitive nerve paths and resilient muscles, driven by a center force pulsating somewhere between the oboes, violins, and violas. It is from there that the ear presumes a mighty stream of energy to spring forth and electrify the musicians up to their fingertips at all times. Frank Martin once said good music worked like "an organism." The New York Philharmonic sounds like that of a blessed dancer, so light-footedly does the orchestra trip across the sound carpet rolled out by Berlioz, a pre-Mahlerian wealth of color; with a sleepwalker's security the orchestral sections follow even the most subtle shifts of the Petite Symphonie.

I have been rehearsing with the Philharmonic for two days, so I already know their magnificence. But I simply could not have imagined that, when it comes down to it, they can play two classes above what I have heard. Inger Dam-Jensen, my Danish colleague, is similarly impressed when, after the break, we are preparing to march into the hall. Normally one allows ladies to go first. Not me. At least not on stage. The old elevator problem! Inger is a tall, slim blonde. I am four feet and three inches. My trotting along behind her would look slightly curious. I am reminded of little Oskar, GŸnter Grass's growth-defying tin drummer. Through five hundred pages the little guy strides ahead at all times. A military image, from the world of parades, the wellversed reader will say. I don't believe it. It is an ironclad aesthetic law, similar to the golden ratio: the shortest must come first. Whoever can remember the cartoon cowboy Lucky Luke and his eternal adversaries, the four Dalton brothers, will know what I mean: the nefarious quartet always confronts Lucky in tiers, standing on the prairie like one of Nebuchadnezzar's ziggurat towers (one might also say like a staggering joke). The same principle holds in the ranks of profiled figures in ancient Egyptian images, in which the small one, whether he, she, or it, always belongs in front of the big one. Then again, in our particular case the idiom "age before beauty" makes the point just as well.

Inger and I are now crossing the orchestra front. The moment of passage from the twilight wings onto the stage is something magical for me, again and again. It is hot and blindingly bright out there. The spotlights create sparkling reflections on the tin and polished wood of the string instruments, while the glittering stage light draws a dark curtain before the rows of seats. One senses rather than sees the murmuring crowd. After one or two steps applause suddenly swells up out of the darkness, much like the first breaker of a rising tide thrown against the shore. The sound gains even more force as Sir Colin climbs the podium and lowers his curly grey head with a smile. But as soon as he turns his back to the audience, this friendly gentleman takes on the aura of an emperor. "He mounts the rostrum, clears his throat and raises his baton; silence falls," Elias Canetti writes of the conductor, and he knows why it must be so and no other way: ". . . since, during the performance, nothing is supposed to exist except this work, for so long is the conductor the ruler of the world."

Sir Colin has lowered the baton, and the orchestra has begun building the score, layer by layer, working towards a mighty march and battle noise. The sentry--in this case, your humble narrator--launches the first stanza into the parquet with corresponding verve: "Ich kann und mag nicht Froehlich sein! / Wenn alle Leute schlafen, / So muss ich wachen, / muss traurig sein." ("I cannot and may not be merry, / when all the world's asleep. / So I must guard / and must be sad.") Inger tries to whisper into my ear that there is no reason for depression since "im Rosengarten, / im gruenen Klee" ("in the rose garden, among the green clover") the maiden awaits her soldier. Besides that, there is God's blessing, which can also be relied upon "on the field," at least for him who believes in it. With this her lovely, enticing soprano glides across a floating cadence of major triads, which Mahler, at the end, tips over into the twilight (an E-minor chord, to be exact). That is when the poor sentry realizes that this tenderly eroticized image of nature is nothing but dream, and the man realizes that trust in God was misplaced, for "He is King / He is the emperor / He leads the war." ("Er ist Koenig! / Er ist Kaiser! / Er fuehrt den Krieg.")

The Philharmonic is establishing this tragedy in such an inspired manner, and our voices bringing it alive in such perfect harmony, that applause starts to drizzle from the balcony at the end of the first song--a mortal sin among traditional classical aficionados. Respect for the work of art demands that the audience wait until the cycle has ended to applaud. Who came up with this rule and how long ago, I don't know. The truth is that it is broken more often than you might think, and, to be honest, I don't mind. Sometimes it is even refreshingly funny: In Chicago once a few colleagues and I were on tour with Mozart vocal pieces, accompanied by the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra. I was singing Leporello's aria to Donna Elvira from Don Giovanni. At the end of the score there is a grand fermata, which requires one note to be held at the same pitch for a rather long time. Into this fermata someone from the audience yelled "Bravo." Without letting my voice break I yelled back "Too early!" I then continued singing, although the last chords of the piece were not audible, since the audience was doubling over in laughter.

Tonight it doesn't go that far. Nevertheless, it gets better and better because fortunately for us singers, and to the great delight of the audience, Colin Davis has decided to allow all songs written in dialogue to be performed as duets. Though the composer did not intend this, the two editors of the Wunderhorn, Clemens Brentano and Achim von Arnim, did. When these poet friends and in-laws presented the first edition of their Old German poem and song collection, it was not pure folk poetry. They had edited the material, smoothed out the rhymes, cut verses, and added entire stanzas at their discretion. Into the "Lied des Verfolgten im Turm" ("Song of the Persecuted in the Tower") a female part was implanted without apology. The seams are visible and audible. The two blocks of lyrics do not add up to a homogeneous whole but are actually two monologues, juxtaposed like parallel action scenes in a movie.

Scene 1 opens in the dungeon. A strip of pale sunlight falls through the bars. The camera zooms onto the emaciated face of a prisoner. He appears composed. He will not eat humble pie. He will resist fate by forsaking all yearning for love and happiness and by conjuring up all the platonic joys of inner immigration. The prisoner rises from his cot, clenches his fists, and sings: "Die Gedanken sind frei, / Wer kann sie erraten? / Sie rauschen vorbei / Wie naechtliche Schatten. / Kein Mensch kann sie wissen, / Kein Jaeger sie schiessen. / Es bleibet dabei, / Die Gedankensind frei." ("Thoughts are free, / Who can guess them? / They stream past us / like shadows in the night. / No man can know them, / No hunter can shoot them. / It remains thus: / Thoughts are free.")

Scene 2 shows the girl squatting on the stairs in front of the ruins, not willing to have any of it. A tear runs across her little cheek while she imagines the lost togetherness: "Im Sommer ist gut lustig sein, / Auf hohen, wilden Heiden. / Dort findet man gruen Plaetzelein. / Mein herzverleibtes Schaetzelein, / Von dir mag ich nicht scheiden." ("In summer it is good to be merry / on high, wild meadows, / where one finds a green little place; / my heart's beloved treasure, / I do not wish to part from you!") And thus it continues in alternating counter cuts until the prisoner speaks his final word: "Und weil Du so klagst, / Der Liebich entsage / . . . / es bleibet dabei, / die Gedanken sind frei. ("And because you lament so / I will renounce love, / . . . / For it remains thus: / Thoughts are free!") The camera flies through the dungeon window, leaving the girl below, a pile of misery againstthe horizon. Cut.

Some wit dubbed the work, a bit glibly but accurately, "a kind of abbreviated Fidelio for choral societies." The dramatically scenic is the basis for all Wunderhorn songs. In "Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt" ("Saint Anthony of Padu‡s Sermon to the Fish") herring, carp, eel, and pike gather to listen to the words of Saint Anthony, clap fins, but, sermon over, swim away as the murderers and robbers they were; "Der Tamboursgesell" ("The Drummer Boy") is sitting in his death cell; the "Rheinlegendchen" ("Little Rhine Legend") is being spun during a walk; the "Irdische Leben" ("Earthly Life") and "Verlorne MŸhll" ("Lost Effort") depict scenes of rural life; in "Trost im UnglŸck" ("Consolation in Misery") a hussar and a girl are bantering in the night; the "Lob des hohen Verstand" ("In Praise of Higher Understanding") negotiates a singing competition between a cuckoo and a nightingale, decided by the referee, naturally a stupid donkey, in favor of the cuckoo. Everything takes place in front of carefully chosen scenery, with the subject matter giving Mahler the greatest possible breadth of compositional variation on the smallest space. In "Wo die schoenen Trompeten blasen" ("Where the Beautiful Trumpets Blow") alone--the ballad of the dead soldier who climbs out of his grave at night to fetch his beloved into his "house of green grass"--he stuffed: elegiac trumpet fifths, accompanying brute marching rhythms, a D-major movement in three-four time; a cantilena in G-flat major; further trumpets in major which in the end dive into the minor-ish. In other places oddities such as false basses, parallel sixths between major episodes, tenth leaps over staccato sixteenths in a dark minor. In "Revelge" ("Reveille"), as Habakuk Traber has observed, there seemed to be "no more rules about how they had to stop and go." No wonder that the entire military noise apparatus comes apart when the fallen drummer drums up the dead bodies of his comrades, leads them into battle, and proudly lets them stand at attention at his sweetheart's house. "Des morgen stehen da die Gebeine / in Reih und Glied, sie stehen wie Leichensteine / Die Trommel steht voran / Trallali, trallalei, trallalera / Dass sie ihn sehen kann" ("In the morning there stand the bones / In rank and file as tombstones. / The drum stands in front / tralali, tralalei, tralala, / so that she can see him.") Mercifully, the song ends here with beats of the drum and caustic clusters of trumpets. I certainly do not want to imagine the face his sweetheart made when she laid eyes on the assembly of zombies. She must have been at least as stunned as the music writer Ernst Decsey, who once addressed Mahler in regard to the most effective but "peculiar

shaping and reshaping of a dominant." The composer curtly replied: "Oh please! Dominant! Take things as naÏvely as they are

intended." Which shows that one should not overtheorize things.

Like Mahler, I am over it. After all, musicology can explain our fascination with the Wunderhorn Lieder only to a limited extent. Let us simply praise Mahler's genius in managing to imprint a modern Weltgefuehl, a sensibility still familiar to us today, onto the anarchic, naÏve, popular texts he was working with. That hopeless "Thrownness" of the late bourgeois individual, deliberated on for volumes by clever heads like Heidegger and Derrida, weaves itself through the cycle. Such loneliness, despair, and painful beauty lies in Mahler's music, such fury, stubbornness, and spite in the face of the frighteningly meaningless humming of the world, that it still touches us in our innermost core today.

"It was so wonderful!"

"Unbelievable!"

"Hey, man, great job!"

"That was music; that was sound!"

"You are the best!"

"No, you're the best!"

Backstage has become one great festival of slaps on the back. The two singers are throwing around compliments and the violins are tossing them back. Celli congratulate clarinets, trombones cuddle basses. Everyone has a smile on his face, and the relatives, friends, and acquaintances who have found their way backstage are equally enthused and overflowing with praise for the virtuosity of their loved ones. I find it wonderful. Sweaty, my veins swollen with adrenaline, I give Micha and Renate my first impressions: "Fantastic . . . how Inger sang the coloratura of Liedlein . . . Colin Davis did the triplet part . . . the pianissimo of the Philharmonic . . . super, went fantastically well . . . thirst . . . have got to get something to drink . . . oh, how nice that you are here . . ." I am talking like a waterfall; the floodgates are open. Now everything has got to come out or I will burst. Seven times we left the stage, seven times they clapped us back out, seven times Sir Colin had to receive a standing ovation with British noblesse, meaning with a slightly bent upper body.

Tony, on the other hand, is not so cool and collected. His anxiety about my debut in his hometown probably outweighed Muhammad Ali's before his first world championship fight against Sonny Liston. Now it is over and Tony is profoundly moved; unlike Ali, he can't find any words. He is waiting for me in my dressing room, and when I return he clasps me firmly to his chest, his eyes moist with emotion. But there isn't much time for

sentimentality in this topsy-turvy madhouse. Musicians are coming and going; journalists are piling in; Markus Sievers, a representative of my German agency, is handing out business cards like Chinese restaurant menus; total strangers are baffling me by giving me the thumbs up, then holding out their programs for my signature, and hey, what do you have to do to get a drink in this place? Just in time, Linda Marder and Charles Cumella appear with a humongous gift basket, which I earned not tonight but rather four days ago, on my birthday. The edible contents would

feed a polar expedition crew, but not the drinks. They are immediately claimed: the beer by Micha, who uses the opportunity to force Charles, a wine drinker, into a debate about the subject of "the global free market and the German law of purity." The champagne is for everyone.

"Somebody open a bottle!" I call out gaily. Tony does not need any more encouragement. Whistling the triumphal march of Aida he shoots the cork against the ceiling and distributes the noble liquid in a super pack of party cups. Then he clicks his heels together, salutes, and raises the plastic

goblet: "Cheers!" I wish it could go on forever, but it can't. There's the "tenminute smile," the opening-night dinner, and tomorrow another performance. The sponsors are already waiting in the foyer. Inger, Sir Colin, and I emerge to hearty applause and are planted next to the buffet for all to see. There is a short greeting, a few words of thanks to the patrons, and then one beholds the triptych of cultivated society, with its clear distribution of labor: one talks, one chews, the artist smiles. But Linda is right. New Yorkers are as entertaining as they are economical in their small talk.

A librarian manages within ten minutes to cover the Vienna Court Opera, Shostakovich's Stalingrad Symphonie, Kafka's Amerika, and Bob Dylan's Christian phase. After twenty minutes more two female doctors have brought me up to date with the latest on the Lewinsky affair. I know more details of John Carpenter's most recent vampire movie than I ever cared to know, and every possible anecdote about Jesse Ventura, the former pro wrestler who just body-slammed the Democrats and the Republicans in the Minnesota governor's election. When the talk comes around to basketball and the honorable New York Knicks I have to check out of the conversation. My legs hurt. I can't stand any longer.

Half an hour later we are sitting in one of the famous Chinatown restaurants. "Original Canton and Szechuan cuisine!" the ma”tre d' enthused, adding, "You have to try our regional specials."

Renate, who once found a dead dog on her plate after a similar recommendation in Taipei, pleads for chop suey. Starving, I am not interested in further details and order a sensational sounding menu translated to me roughly as "thirteen delicacies from the lotus garden of the seventh concubine of the emperor so and so." I am not disappointed. Soon there are nimble waiters flitting about, arranging bowls, pans, and skillets above the can of Sterno. One brings crab and black beans; another marinated pork, fish, and beef meatballs; the third brings soy sprouts, carrots, and leeks with a multicolored dip. Soon we all dig in. Only Sir Colin does not get to eat. He is sitting next to Tony, and Tony is talking about his favorite subject, putting Schubert in between the maestro and his sweet and sour chicken, "Schumann . . . Brahms . . . Wagner . . . the genius of Romantic music. But can you explain what Schönberg's idea was?" I am unable to make out whether Colin Davis offers him a satisfying response.

We close down the evening in a smaller circle at Tavern on the Green. The Central Park bar is not exactly a refuge of coziness: the interior is showy and cold, like something right out of Bonfire of the Vanities. Nothing but chrome, mirrored walls, and overly bright lights, and the prices are shrill as well. But it's one of the few places you can eat and smoke--something the EU fraction of our little group insisted on--and Markus, the guy from my German agency, is simply not to be deterred from playing the big shot tonight: "Come on guys, let's go inside. This is on me."

Well, that was before we got in. After a few rounds his head gleams tomato red at the bar as he digs through his wallet and discusses the bill with the staff, while we at the table discuss whether to bail him out or leave him there to do the dishes. My brother, always one for a bit of wisdom after a few drinks, cites Heiner MŸller: "Man is but dirt, his life but a great laughter." He is for washing dishes. We could counter with Kant's categorical imperative, which, as most everyone knows, simply paraphrases the old folk wisdom: "Do unto others as you would have them do unto you." Micha pays up generously, for Renate and for me as well, but he still murmurs in my ear the whole way home: "Reason gives rise to monsters. You hear? Monsters! Nothing good will come of it."

Well, we're all familiar with the dialectic of the Enlightenment. As long as Horkheimer and Adorno stay out of my dreams, anything is fine with me. And tonight the great sandman is conciliatory. No nightmare, no construction crew, no vacuum can wake me up. I sleep deeply and soundly until noon.

Upon waking up I find a greeting from Renate and Micha on my night table: "Checking out museums today. See you later. Have a nice day. PS: You must look at the paper!" I decide to take it slow and have breakfast in the hotel. The hunters and gatherers are already out stalking again, and the restaurant is accordingly empty. Very nice. I make myself comfortable in a corner and order eggs, bacon, toast, lots of coffee, and the morning papers. When my name appears in fat print right under that of Sir Colin my heart pumps un poco presto. Alright then. A deep inhalation; then slooowly exhale. All is well. In fact, it couldn't be any better. They praise Colin Davis, they praise the Philharmonic, they bestow highest praise upon the total work of art, but they especially praise "the little German singer with the big voice." Even the Times's incorruptible Mr. Tommasini is delighted. He writes that from now on they'll want to hear my marvelous baritone more often in New York.

The waiter appears and puts a telephone next to the orange juice.

It's Linda.

"Good morning, Tommy. Have you already looked at the paper?"

"Just now."

"And? Isn't it fantastic? Everyone is blown away by your voice. Tomorrow you will be a famous singer all over America."

"Great, does that mean I get to go on Jay Leno?"

"That means a lot more. It means you can choose where you want to perform, with whom you want to perform, and what program. Avery Fisher Hall has already called and asked to schedule an evening of German Liederabend. Tommy, you have done it. Here we say about New York: if you can make it there, you'll make it anywhere. Whoever comes through New York has nothing to worry about. We will get lots of work."

Linda always means what she says and knows what she's doing. Nevertheless, I want to ask the waiter to pinch me hard, for I can't believe this is really happening. I let myself sink into the banquette pillows with a sigh. The window frames the usual three o'clock performance: joggers grimly stomping across the pavement, chubby schoolkids with sneakers as large as shoe boxes, two homeless people dozing in front of their cardboard caves, businesspeople with fluttering coats striding out of the fine Broadway restaurants into the office towers. A group of black street sweepers strolls laughing into the park, and at the newsstand the cabdrivers are getting bored. Men from Ukraine and Yemen, from Pakistan or Gabon, men who are looking for luck and find it as rarely as a tourist successfully navigates the tangled streets downtown. But luck has never been shy with me. Maybe that's why I often feel as if I am an actor in a movie, a jolly piece but a little surreal, directed not, say, by Billy Wilder, but by Luis Bu–uel. I like Bu–uel, and I like this weightless and slightly insane mood.

This crazy luck was already in the air as we prepared to leave Hamburg: in the next three weeks I would be singing the two most important concerts of my life, on stage in New York and Boston with the best orchestras of the United States. It was exactly what I had always wanted, and I knew I was up to it. Just before we left, the Echo Classic Award 1998 was handed to me in the Hamburg Music Hall. This was like winning the German Grammy for Best Singer. It is a beautiful thing, this achievement, though the trophy itself is heavy and ugly, an old piece of iron we chose to store in my parents' car. My parents were there when I won, sitting proudly in the hall, and they were there to bid good-bye to their America-bound offspring--my mother, as usual, with practical advice:

"Don't get lost, now, no nonsense, and don't have Thomas's dirty laundry washed by the hotel. I'd rather do it myself."

My father with decisive last questions:

"Boys, have you got your passports?"

" 'Course!"

"And your boarding passes?"

"Sure!"

"Better check again. Micha is such an old scatterbrain."

"Don't worry, Papa. It's all there."

'Well, I hope so! Take care then, and call as soon as you've arrived in one piece."

"Otherwise the doctor will call!"

"You are and always will be a clod pole."

"You are the best."

"Okay, enough now. 'Bye my dears."

High above the airfield stretches an azure sheet streaked with cirrus and shot through with sunshine. Golden is the month of October, and the Quasthoff brothers are in a holiday mood. It isn't often that Micha has time to accompany me on a concert trip, and this one is especially nice because almost fourteen free days lie between the appearances in Boston and New York.

I carry those days with me like a precious photo album. There is a rollicking dinner at the end of which Seiji Ozawa asked Micha with a laugh: "Is your brother always this crazy?" And there is the excursion to Cape Cod, the gliding along Highway 93 under a radiant sky, the Indian summer rushing by in psychedelic shades of red and yellow, and our friend Felicitas tooting Loewe ballads through a rolled-up map. There are the colorfully painted wooden houses and cranberry fields of Rhode Island, the marsh lawns and dune strips behind the channel that separate Cape Cod from the mainland, and finally, in Provincetown, the magnificent ocean and lots of wind. Wave after wave rushes towards the beach in foam-crowned Hockney blue while we brace ourselves against the gusts at forty-five-degree angles, like crooked poles. Then there's the bay of Plymouth where the first Pilgrims set foot in 1620. On the left a model of the Mayflower is anchored, and crazy Tony jumps around the monumental Rock proclaiming with a grin that this gruesome hunk of granite should actually be a giant doughnut.

Then I see us in New York, worried and incredibly tired at JFK because Renate's flight is four and a half hours delayed. Not three hours after that there we are at the Knitting Factory, beside ourselves with excitement because Steven Bernstein's quintet, Sex Mob Featuring John Medeski is performing "John Barry's Music from James Bond Films." I see us atop the Empire State Building and strolling through Little Odessa, where the blocks of houses almost fall into the ocean. I see us standing rapt before Mark Rothko's fields of color, and I see how Renate snaps a picture of the fraternal couple in front of Carnegie Hall, at which point I hear myself call out like the young Gerd SchrÖeder, "I want in there!" (in the chancellor's office). But the most beautiful memory picture by far goes back to Birdland. We are celebrating my thirty-ninth birthday. From the stage a thirty-man New York allstar band is peppering us with knife-sharp riffs, while heads and feet are moving ever bolder below in an Afro-Cuban rhythmic frenzy. When midnight strikes, the band pauses and the staff presents me with a bottle of champagne! Renate has conjured up a birthday cake with sparklers and everyone is wishing me well.

Today, of course, the Avery Fisher Hall concerts, so important for my career, have a place of honor in my American album as well. Every time I open it I am reminded of my parents and the fact that this career would never have been possible without their love, their trust, and their support. It means so much to them to see me live a successful, independent, and, most of all, happy life. After all, I wasn't a sure thing when my mother gave birth, on November 9, 1959, in the Bernwards-Hospital of Hildesheim, to one of twelve thousand thalidomide children.

Media reviews

"If Thomas Quasthoff appeared on an awards show, he would play the master of ceremonies. If he were an animal, he would be a lion, king of the jungle. If he were to play a romantic lead, he'd be the inventively eloquent Cyrano. But Quasthoff, blessed with a bass-baritone voice as soaring and generous as his own spirit, has the great good fortune to play them all--from the playful poet singing lieder to the soulful and magisterial prophet Elijah. Catch him during at unguarded moment offstage, and he'll even indulge in a little Dixieland scat. For a man born with such severe physical limitations, it appears, in fact, that there are no limits."

--Time

"With an appearance and life story so compellingly strange, it would be easy for the miracle of his perseverance and triumph, or the miracle of his perseverance and triumph, or the miracle of such a powerful and deep voice emerging from such a small body, to overwhelm the concert experience. Instead, if there is anything miraculous about Quasthoff, it is that a few minutes into a recital you stop thinking about his physique . . . He channels all of his feelings into his expressive face and subtly shaded voice . . . He holds you with his ability to communicate the mood and meaning of a song."

--The New York Times Magazine

About the author

More Copies for Sale

The Voice: A Memoir

by Quasthoff, Thomas

- Used

- Hardcover

- Condition

- Used - Acceptable

- Binding

- Hardcover

- ISBN 10 / ISBN 13

- 9780375424069 / 0375424067

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Eugene , Oregon, United States

- Item Price

-

A$6.19A$6.19 shipping to USA

Show Details

The Voice : A Memoir

by Thomas Quasthoff

- Used

- good

- Hardcover

- Condition

- Used - Good

- Binding

- Hardcover

- ISBN 10 / ISBN 13

- 9780375424069 / 0375424067

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Seattle, Washington, United States

- Item Price

-

A$9.40FREE shipping to USA

Show Details

The Voice: A Memoir

by Quasthoff, Thomas

- Used

- very good

- Paperback

- Condition

- Used - Very Good

- Binding

- Paperback

- ISBN 10 / ISBN 13

- 9780375424069 / 0375424067

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

GORING BY SEA, West Sussex, United Kingdom

- Item Price

-

A$12.53A$16.67 shipping to USA

Show Details

The Voice: A Memoir

by Quasthoff, Thomas

- Used

- Hardcover

- Condition

- UsedGood

- Binding

- Hardcover

- ISBN 10 / ISBN 13

- 9780375424069 / 0375424067

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Fort Worth, Texas, United States

- Item Price

-

A$10.12FREE shipping to USA

Show Details

The Voice : A Memoir

by Quasthoff, Thomas

- Used

- Condition

- Used - Very Good

- ISBN 10 / ISBN 13

- 9780375424069 / 0375424067

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Mishawaka, Indiana, United States

- Item Price

-

A$10.46FREE shipping to USA

Show Details

The Voice : A Memoir

by Quasthoff, Thomas

- Used

- Condition

- Used - Very Good

- ISBN 10 / ISBN 13

- 9780375424069 / 0375424067

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Mishawaka, Indiana, United States

- Item Price

-

A$10.46FREE shipping to USA

Show Details

The Voice : A Memoir

by Quasthoff, Thomas

- Used

- Condition

- Used - Good

- ISBN 10 / ISBN 13

- 9780375424069 / 0375424067

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Reno, Nevada, United States

- Item Price

-

A$10.46FREE shipping to USA

Show Details

The Voice: A Memoir

by Quasthoff, Thomas

- Used

- very good

- Hardcover

- first

- Condition

- Used - Very Good

- Edition

- First Edition

- Binding

- Hardcover

- ISBN 10 / ISBN 13

- 9780375424069 / 0375424067

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Portland, Oregon, United States

- Item Price

-

A$10.86A$10.09 shipping to USA

Show Details

The Voice: A Memoir

by Thomas Quasthoff

- Used

- good

- Hardcover

- Condition

- Used - Good

- Binding

- Hardcover

- ISBN 10 / ISBN 13

- 9780375424069 / 0375424067

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

HOUSTON, Texas, United States

- Item Price

-

A$13.64FREE shipping to USA

Show Details

The Voice: A Memoir

by Quasthoff, Thomas

- Used

- Condition

- Used - Good

- ISBN 10 / ISBN 13

- 9780375424069 / 0375424067

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Frederick, Maryland, United States

- Item Price

-

A$13.76A$6.19 shipping to USA

Show Details

Remote Content Loading...

Hang on… we’re fetching the requested page.

Book Conditions Explained

Biblio’s Book Conditions

-

As NewThe book is pristine and free of any defects, in the same condition as when it was first newly published.

-

Fine (F)A book in fine condition exhibits no flaws. A fine condition book closely approaches As New condition, but may lack the crispness of an uncirculated, unopened volume.

-

Near Fine (NrFine or NF)Almost perfect, but not quite fine. Any defect outside of shelf-wear should be noted.

-

Very Good (VG)A used book that does show some small signs of wear - but no tears - on either binding or paper. Very good items should not have writing or highlighting.

-

Good (G or Gd.)The average used and worn book that has all pages or leaves present. ‘Good’ items often include writing and highlighting and may be ex-library. Any defects should be noted. The oft-repeated aphorism in the book collecting world is “good isn’t very good.”

-

FairIt is best to assume that a “fair” book is in rough shape but still readable.

-

Poor (P)A book with significant wear and faults. A poor condition book can still make a good reading copy but is generally not collectible unless the item is very scarce. Any missing pages must be specifically noted.