De revolutionibus orbium coelestium libri VI : habes in hoc opere iam recens nato, & ædito, studiose lector, motus stellarum, tam fixarum, quàm erraticarum, cum ex ueteribus, tum etiam ex recentibus obseruationibus restitutos : & nouis insuper ac admirabilibus hypothesibus ornatos : habes etiam tabulas expeditissimas, ex quibus eosdem ad quoduis tempus quàm facilli me calculare poteris : igitur eme, lege, fruere

by Copernicus, Nicolaus (1473-1543)

- Used

- Fine

- Hardcover

- first

- Condition

- Fine

- Seller

-

Chevy Chase, Maryland, United States

Payment Methods Accepted

About This Item

Nuremberg: Johannes Petreius, 1543. FIRST EDITION, and a very fine and crisp copy. Hardcover. Fine. Bound in attractive, contemporary Parisian calf with some discreet repairs. The boards are blind-ruled and adorned with gold-tooled ornaments. This is one of very few to have appeared on the market in a contemporary binding. The text is in excellent condition, with just minor blemishes (small early erasure of an ownership inscription on the title just slightly touching the "D." in the date. Light damp-staining to first six leaves.) Collation as in Horblit; this copy without the errata leaf -printed separately and later- that is found in a minority of copies (about 20 percent). Preserved in a morocco-backed box. Provenance: At the foot of the title-page, an early signature has been thoroughly lined through. 17th- or 18th-century inscription on title of the Jesuit College of Paris. Bookplate of Gustavus Wynne Cook (1867-1940, amateur astronomer, collector, and benefactor of the Franklin Institute). Franklin Institute bookplate. Sold at Sotheby Parke-Bernet, New York, November 1977, lot 85. Purchased by Pierre Berès at Sotheby's London, 21 October 1980 and sold to a prominent Spanish private collector.

"The earliest of the three books of science that most clarified the relationship of man and his universe (along with Newton's Principia and Darwin's Origin of Species)."-Dibner, Heralds of Science, 3. This work is the foundation of the heliocentric theory of the planetary system and the most important scientific text of the 16th century.

Copernicus began to work on astronomy on his own. Sometime between 1510 and 1514 he wrote an essay that has come to be known as the Commentariolus that introduced his new cosmological idea, the heliocentric system, and he sent copies to various astronomers. He continued making astronomical observations whenever he could, hampered by the poor position for observations in Frombork and his many pressing responsibilities as canon. Nevertheless, he kept working on his manuscript of On the Revolutions. In 1539 a young mathematician named Georg Joachim Rheticus (1514-1574) from the University of Wittenberg came to study with Copernicus. Rheticus brought Copernicus books in mathematics, in part to show Copernicus the quality of printing that was available in the German-speaking cities. He published an introduction to Copernicus's ideas, the Narratio prima (First Report). Most importantly, he convinced Copernicus to publish On the Revolutions. Rheticus oversaw most of the printing of the book, and on 24 May 1543 Copernicus held a copy of the finished work on his deathbed.

It is impossible to date when Copernicus first began to espouse the heliocentric theory. Had he done so during his lecture in Rome, such a radical theory would have occasioned comment, but there was none, so it is likely that he adopted this theory after 1500. His first heliocentric writing was his Commentariolus. It was a small manuscript that was circulated but never printed. We do not know when he wrote this, but a professor in Cracow cataloged his books in 1514 and made reference to a "manuscript of six leaves expounding the theory of an author who asserts that the earth moves while the sun stands still" (Rosen, 1971, 343). Thus, Copernicus probably adopted the heliocentric theory sometime between 1508 and 1514. Rosen (1971, 345) suggested that Copernicus's "interest in determining planetary positions in 1512-1514 may reasonably be linked with his decisions to leave his uncle's episcopal palace in 1510 and to build his own outdoor observatory in 1513." In other words, it was the result of a period of intense concentration on cosmology that was facilitated by his leaving his uncle and the attendant focus on church politics and medicine.

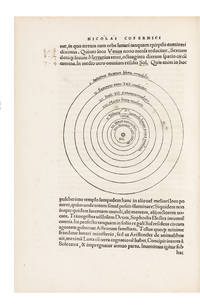

In the Commentariolus Copernicus listed assumptions that he believed solved the problems of ancient astronomy. He stated that the earth is only the center of gravity and center of the moon's orbit; that all the spheres encircle the sun, which is close to the center of the universe; that the universe is much larger than previously assumed, and the earth's distance to the sun is a small fraction of the size of the universe; that the apparent motion of the heavens and the sun is created by the motion of the earth; and that the apparent retrograde motion of the planets is created by the earth's motion. Although the Copernican model maintained epicycles moving along the deferent, which explained retrograde motion in the Ptolemaic model, Copernicus correctly explained that the retrograde motion of the planets was only apparent not real, and its appearance was due to the fact that the observers were not at rest in the center. The work dealt very briefly with the order of the planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, the only planets that could be observed with the naked eye), the triple motion of the earth (the daily rotation, the annual revolution of its center, and the annual revolution of its inclination) that causes the sun to seem to be in motion, the motions of the equinoxes, the revolution of the moon around the earth, and the revolution of the five planets around the sun.

The Commentariolus was only intended as an introduction to Copernicus's ideas, and he wrote "the mathematical demonstrations intended for my larger work should be omitted for brevity's sake...". In a sense it was an announcement of the greater work that Copernicus had begun. The Commentariolus was never published during Copernicus's lifetime, but he sent manuscript copies to various astronomers and philosophers. He received some discouragement because the heliocentric system seemed to disagree with the Bible, but mostly he was encouraged.

Although Copernicus's involvement with official attempts to reform the calendar was limited to a no longer extant letter, that endeavor made a new, serious astronomical theory welcome. Fear of the reaction of ecclesiastical authorities was probably the least of the reasons why he delayed publishing his book. The most important reasons for the delay was that the larger work required both astronomical observations and intricate mathematical proofs. His administrative duties certainly interfered with both the research and the writing. He was unable to make the regular observations that he needed and Frombork, which was often fogged in, was not a good place for those observations. Moreover, as Gingerich (1993, 37) pointed out, [Copernicus] was far from the major international centers of printing that could profitably handle a book as large and technical as De revolutionibus. On the other hand, his manuscript was still full of numerical inconsistencies, and he knew very well that he had not taken complete advantage of the opportunities that the heliocentric viewpoint offered...Furthermore, Copernicus was far from academic centers, thereby lacking the stimulation of technically trained colleagues with whom he could discuss his work.

The manuscript of On the Revolutions was basically complete when Rheticus came to visit him in 1539. The work comprised six books. The first book, the best known, discussed what came to be known as the Copernican theory and what is Copernicus's most important contribution to astronomy, the heliocentric universe (although in Copernicus's model, the sun is not truly in the center). Book 1 set out the order of the heavenly bodies about the sun: "[The sphere of the fixed stars] is followed by the first of the planets, Saturn, which completes its circuit in 30 years. After Saturn, Jupiter accomplishes its revolution in 12 years. Mars revolves in 2 years. The annual revolution takes the series' fourth place, which contains the earth...together with the lunar sphere as an epicycle. In the fifth place Venus returns in 9 months. Lastly, the sixth place is held by Mercury, which revolves in a period of 80 days" (Revolutions, 21-22). This established a relationship between the order of the planets and their periods, and it made a unified system. This may be the most important argument in favor of the heliocentric model as Copernicus described it. It was far superior to Ptolemy's model, which had the planets revolving around the earth so that the sun, Mercury, and Venus all had the same annual revolution. In book 1 Copernicus also insisted that the movements of all bodies must be circular and uniform, and noted that the reason they may appear nonuniform to us is "either that their circles have poles different [from the earth's] or that the earth is not at the center of the circles on which they revolve" (Revolutions, 11). Particularly notable for Copernicus was that in Ptolemy's model the sun, the moon, and the five planets seemed ironically to have different motions from the other heavenly bodies and it made more sense for the small earth to move than the immense heavens. But the fact that Copernicus turned the earth into a planet did not cause him to reject Aristotelian physics, for he maintained that "land and water together press upon a single center of gravity; that the earth has no other center of magnitude; that, since earth is heavier, its gaps are filled with water..." (Revolutions, 10). As Aristotle had asserted, the earth was the center toward which the physical elements gravitate. This was a problem for Copernicus's model, because if the earth was no longer the center, why should elements gravitate toward it?

The second book of On the Revolutions elaborated the concepts in the first book; book 3 dealt with the precession of the equinoxes and solar theory; book 4 dealt with the moon's motions; book 5 dealt with the planetary longitude and book 6 with latitude. Copernicus depended very much on Ptolemy's observations, and there was little new in his mathematics. He was most successful in his work on planetary longitude, which, as Swerdlow and Neugebauer commented, was "Copernicus's most admirable, and most demanding, accomplishment...It was above all the decision to derive new elements for the planets that delayed for nearly half a lifetime Copernicus's continuation of his work - nearly twenty years devoted to observation and then several more to the most tedious kind of computation - and the result was recognized by his contemporaries as the equal of Ptolemy's accomplishment, which was surely the highest praise for an astronomer." Surprisingly, given that the elimination of the equant was so important in the Commentariolus, Copernicus did not mention it in book 1, but he sought to replace it with an epicycle throughout On the Revolutions. Nevertheless, he did write in book 5 when describing the motion of Mercury:

...the ancients allowed the epicycle to move uniformly only around the equant's center. This procedure was in gross conflict with the true center [of the epicycle's motion], its relative [distances], and the prior centers of both [other circles]...However, in order that this last planet too may be rescued from the affronts and pretenses of its detractors, and that its uniform motion, no less than that of the other aforementioned planets, may be revealed in relation to the earth's motion, I shall attribute to it too, [as the circle mounted] on its eccentric, an eccentric instead of the epicycle accepted in antiquity (Revolutions, 278-79)." (Sheila Rabin, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

"The earliest of the three books of science that most clarified the relationship of man and his universe (along with Newton's Principia and Darwin's Origin of Species)."-Dibner, Heralds of Science, 3. This work is the foundation of the heliocentric theory of the planetary system and the most important scientific text of the 16th century.

Copernicus began to work on astronomy on his own. Sometime between 1510 and 1514 he wrote an essay that has come to be known as the Commentariolus that introduced his new cosmological idea, the heliocentric system, and he sent copies to various astronomers. He continued making astronomical observations whenever he could, hampered by the poor position for observations in Frombork and his many pressing responsibilities as canon. Nevertheless, he kept working on his manuscript of On the Revolutions. In 1539 a young mathematician named Georg Joachim Rheticus (1514-1574) from the University of Wittenberg came to study with Copernicus. Rheticus brought Copernicus books in mathematics, in part to show Copernicus the quality of printing that was available in the German-speaking cities. He published an introduction to Copernicus's ideas, the Narratio prima (First Report). Most importantly, he convinced Copernicus to publish On the Revolutions. Rheticus oversaw most of the printing of the book, and on 24 May 1543 Copernicus held a copy of the finished work on his deathbed.

It is impossible to date when Copernicus first began to espouse the heliocentric theory. Had he done so during his lecture in Rome, such a radical theory would have occasioned comment, but there was none, so it is likely that he adopted this theory after 1500. His first heliocentric writing was his Commentariolus. It was a small manuscript that was circulated but never printed. We do not know when he wrote this, but a professor in Cracow cataloged his books in 1514 and made reference to a "manuscript of six leaves expounding the theory of an author who asserts that the earth moves while the sun stands still" (Rosen, 1971, 343). Thus, Copernicus probably adopted the heliocentric theory sometime between 1508 and 1514. Rosen (1971, 345) suggested that Copernicus's "interest in determining planetary positions in 1512-1514 may reasonably be linked with his decisions to leave his uncle's episcopal palace in 1510 and to build his own outdoor observatory in 1513." In other words, it was the result of a period of intense concentration on cosmology that was facilitated by his leaving his uncle and the attendant focus on church politics and medicine.

In the Commentariolus Copernicus listed assumptions that he believed solved the problems of ancient astronomy. He stated that the earth is only the center of gravity and center of the moon's orbit; that all the spheres encircle the sun, which is close to the center of the universe; that the universe is much larger than previously assumed, and the earth's distance to the sun is a small fraction of the size of the universe; that the apparent motion of the heavens and the sun is created by the motion of the earth; and that the apparent retrograde motion of the planets is created by the earth's motion. Although the Copernican model maintained epicycles moving along the deferent, which explained retrograde motion in the Ptolemaic model, Copernicus correctly explained that the retrograde motion of the planets was only apparent not real, and its appearance was due to the fact that the observers were not at rest in the center. The work dealt very briefly with the order of the planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, the only planets that could be observed with the naked eye), the triple motion of the earth (the daily rotation, the annual revolution of its center, and the annual revolution of its inclination) that causes the sun to seem to be in motion, the motions of the equinoxes, the revolution of the moon around the earth, and the revolution of the five planets around the sun.

The Commentariolus was only intended as an introduction to Copernicus's ideas, and he wrote "the mathematical demonstrations intended for my larger work should be omitted for brevity's sake...". In a sense it was an announcement of the greater work that Copernicus had begun. The Commentariolus was never published during Copernicus's lifetime, but he sent manuscript copies to various astronomers and philosophers. He received some discouragement because the heliocentric system seemed to disagree with the Bible, but mostly he was encouraged.

Although Copernicus's involvement with official attempts to reform the calendar was limited to a no longer extant letter, that endeavor made a new, serious astronomical theory welcome. Fear of the reaction of ecclesiastical authorities was probably the least of the reasons why he delayed publishing his book. The most important reasons for the delay was that the larger work required both astronomical observations and intricate mathematical proofs. His administrative duties certainly interfered with both the research and the writing. He was unable to make the regular observations that he needed and Frombork, which was often fogged in, was not a good place for those observations. Moreover, as Gingerich (1993, 37) pointed out, [Copernicus] was far from the major international centers of printing that could profitably handle a book as large and technical as De revolutionibus. On the other hand, his manuscript was still full of numerical inconsistencies, and he knew very well that he had not taken complete advantage of the opportunities that the heliocentric viewpoint offered...Furthermore, Copernicus was far from academic centers, thereby lacking the stimulation of technically trained colleagues with whom he could discuss his work.

The manuscript of On the Revolutions was basically complete when Rheticus came to visit him in 1539. The work comprised six books. The first book, the best known, discussed what came to be known as the Copernican theory and what is Copernicus's most important contribution to astronomy, the heliocentric universe (although in Copernicus's model, the sun is not truly in the center). Book 1 set out the order of the heavenly bodies about the sun: "[The sphere of the fixed stars] is followed by the first of the planets, Saturn, which completes its circuit in 30 years. After Saturn, Jupiter accomplishes its revolution in 12 years. Mars revolves in 2 years. The annual revolution takes the series' fourth place, which contains the earth...together with the lunar sphere as an epicycle. In the fifth place Venus returns in 9 months. Lastly, the sixth place is held by Mercury, which revolves in a period of 80 days" (Revolutions, 21-22). This established a relationship between the order of the planets and their periods, and it made a unified system. This may be the most important argument in favor of the heliocentric model as Copernicus described it. It was far superior to Ptolemy's model, which had the planets revolving around the earth so that the sun, Mercury, and Venus all had the same annual revolution. In book 1 Copernicus also insisted that the movements of all bodies must be circular and uniform, and noted that the reason they may appear nonuniform to us is "either that their circles have poles different [from the earth's] or that the earth is not at the center of the circles on which they revolve" (Revolutions, 11). Particularly notable for Copernicus was that in Ptolemy's model the sun, the moon, and the five planets seemed ironically to have different motions from the other heavenly bodies and it made more sense for the small earth to move than the immense heavens. But the fact that Copernicus turned the earth into a planet did not cause him to reject Aristotelian physics, for he maintained that "land and water together press upon a single center of gravity; that the earth has no other center of magnitude; that, since earth is heavier, its gaps are filled with water..." (Revolutions, 10). As Aristotle had asserted, the earth was the center toward which the physical elements gravitate. This was a problem for Copernicus's model, because if the earth was no longer the center, why should elements gravitate toward it?

The second book of On the Revolutions elaborated the concepts in the first book; book 3 dealt with the precession of the equinoxes and solar theory; book 4 dealt with the moon's motions; book 5 dealt with the planetary longitude and book 6 with latitude. Copernicus depended very much on Ptolemy's observations, and there was little new in his mathematics. He was most successful in his work on planetary longitude, which, as Swerdlow and Neugebauer commented, was "Copernicus's most admirable, and most demanding, accomplishment...It was above all the decision to derive new elements for the planets that delayed for nearly half a lifetime Copernicus's continuation of his work - nearly twenty years devoted to observation and then several more to the most tedious kind of computation - and the result was recognized by his contemporaries as the equal of Ptolemy's accomplishment, which was surely the highest praise for an astronomer." Surprisingly, given that the elimination of the equant was so important in the Commentariolus, Copernicus did not mention it in book 1, but he sought to replace it with an epicycle throughout On the Revolutions. Nevertheless, he did write in book 5 when describing the motion of Mercury:

...the ancients allowed the epicycle to move uniformly only around the equant's center. This procedure was in gross conflict with the true center [of the epicycle's motion], its relative [distances], and the prior centers of both [other circles]...However, in order that this last planet too may be rescued from the affronts and pretenses of its detractors, and that its uniform motion, no less than that of the other aforementioned planets, may be revealed in relation to the earth's motion, I shall attribute to it too, [as the circle mounted] on its eccentric, an eccentric instead of the epicycle accepted in antiquity (Revolutions, 278-79)." (Sheila Rabin, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

Reviews

(Log in or Create an Account first!)

Details

- Bookseller

- Liber Antiquus

(US)

- Bookseller's Inventory #

- 4339

- Title

- De revolutionibus orbium coelestium libri VI : habes in hoc opere iam recens nato, & ædito, studiose lector, motus stellarum, tam fixarum, quàm erraticarum, cum ex ueteribus, tum etiam ex recentibus obseruationibus restitutos : & nouis insuper ac admirabilibus hypothesibus ornatos : habes etiam tabulas expeditissimas, ex quibus eosdem ad quoduis tempus quàm facilli me calculare poteris : igitur eme, lege, fruere

- Author

- Copernicus, Nicolaus (1473-1543)

- Format/Binding

- Hardcover

- Book Condition

- Used - Fine

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Edition

- FIRST EDITION, and a very fine and crisp copy

- Publisher

- Johannes Petreius

- Place of Publication

- Nuremberg

- Date Published

- 1543

- Weight

- 0.00 lbs

Terms of Sale

Liber Antiquus

Returns accepted within 7 days of receipt. All returns must be packed, insured, and shipped as they were sent. All returns must arrive safely and in the condition in which they were sent before a refund will be issued.

About the Seller

Liber Antiquus

Biblio member since 2020

Chevy Chase, Maryland

About Liber Antiquus

Liber Antiquus sells early printed books (15th to 18th century) and early manuscripts in a number of fields. We have been in business for 22 years and are a member of ABAA and ILAB.

Glossary

Some terminology that may be used in this description includes:

- A.N.

- The book is pristine and free of any defects, in the same condition as ...

- Calf

- Calf or calf hide is a common form of leather binding. Calf binding is naturally a light brown but there are ways to treat the...

- New

- A new book is a book previously not circulated to a buyer. Although a new book is typically free of any faults or defects, "new"...

- First Edition

- In book collecting, the first edition is the earliest published form of a book. A book may have more than one first edition in...

- Fine

- A book in fine condition exhibits no flaws. A fine condition book closely approaches As New condition, but may lack the...

- Leaves

- Very generally, "leaves" refers to the pages of a book, as in the common phrase, "loose-leaf pages." A leaf is a single sheet...

- Errata

- Errata: aka Errata Slip A piece of paper either laid in to the book correcting errors found in the printed text after being...

- Poor

- A book with significant wear and faults. A poor condition book is still a reading copy with the full text still readable. Any...

- Bookplate

- Highly sought after by some collectors, a book plate is an inscribed or decorative device that identifies the owner, or former...

- Crisp

- A term often used to indicate a book's new-like condition. Indicates that the hinges are not loosened. A book described as crisp...