Experiments and Observations on the Gastric Juice, and the Physiology of Digestion

by BEAUMONT, William

- Used

- first

- Condition

- See description

- Seller

-

Koebenhavn V, Denmark

Payment Methods Accepted

About This Item

"THE MOST IMPORTANT PRESENTATION COPY EXTANT".

First edition, inscribed by Beaumont to James W. Kingsbury, of "the most important study of digestion before Pavlov" (Garrison-Morton), this is "the first great American contribution to physiology" and "the most important presentation copy extant" (). Sir William Osler called Beaumont (1785-1853) "the pioneer physiologist of the United States, and the first to make a contribution of enduring value. His work remains a model of patient, persevering research." "While stationed at Fort Mackinac, near Michilimackinac, on Mackinac Island, Michigan, close to the Canadian border - then and now an extremely remote location - Beaumont had been presented with a unique opportunity in the person of one of his patients, the young French Canadian soldier Alexis St. Martin (1797?-1880), who was left with a permanent gastric fistula after suffering a gunshot wound to the stomach. Beaumont's experiments and observations, conducted between 1825 and 1831, conclusively established the chemical nature of digestion, the presence and role of hydrochloric acid in the stomach, the temperature of the stomach during digestion, the movement of the stomach walls and the relative digestibility of certain foods - all of which revolutionized current theories of the physiology of digestion" (ibid.). Beaumont wrote of St. Martin, "When he lies on the opposite side, I can look directly into the cavity of the stomach, and almost see the process of digestion." Beaumont's scientific advisors urged him to haveExperiments and Observations on the Gastric Juiceissued by established medical publishers such as Lippincott in Philadelphia, but he decided to self-publish his book. He had it typeset at the press of the town newspaper in Plattsburgh, New York, where he practised medicine, probably because he thought the work could be done more quickly and cheaply there. According to a letter of 4 December 1833 from Beaumont to Surgeon-General Joseph Lovell, the dedicatee, the first edition consisted of 1000 copies, although Beaumont's nephew later claimed that 3000 copies had been printed. Most of the first edition had the Plattsburgh imprint, but there was a smaller second issue with the imprint 'Boston: Lilly, Wait, and Company'. "Only one other presentation copy of this work is recorded: the Haskell F. Norman copy, which sold at Christie's NY in 1998. That was one of fifty copies which Beaumont had bound in full leather. Considering normal book production practice, it is likely that the special full-leather copies were produced after the main edition. The Norman copy was inscribed by Beaumont to William Dunlap, whose relationship with Beaumont is unknown" ().

Provenance: James W. Kingsbury (1813-81) (inscription on title in Beaumont's hand); Joseph W. Kingsbury; Scribner Rare Books Shop (1947); Thomas W. Streeter; sold Bonham's NY, 27 June 2006, lot 3046, $38,838.

"Nestled along the clear blue straits between the great lakes called Michigan and Huron is an oblong and verdant island. Centuries ago, the Chippewa and Ottawa tribes named it Michilimackinac, or 'the Great Turtle'; [it is] referred to today as Mackinac but pronounced 'Mackinaw' ... In 1670, the French Jesuit missionary Father Jacques Marquette and his intrepid interpreter Louis Joliet fled St. Ignace, Michigan, to settle on the 'Great Turtle' in the name of their homeland. Less than a century later, in 1759, the British took control of the island from the French and, in 1783, after signing the Treaty of Paris, Great Britain relinquished it to the fledgling United States, which had to defend and regain it during the War of 1812. The French pursued fur trapping there with vigor and cunning. But it was John Jacob Astor, the first US multimillionaire, who put Mackinac Island on the map in 1817, when Michigan was admitted to the Union and Astor chose the island as the main trading post of his fabled American Fur Company, a pelt empire that spanned from the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River.

"Every June, the American Fur Company hosted a convention on Mackinac for thousands of trappers eager to sell or barter the bounty they had hunted the previous winter. The rest of the year, the island's population hovered at a mere 500. Situated on the southeast cliff a few hundred feet above the shoreline was a limestone fortress built by the British in 1761 and subsequently occupied by the US Army to protect the island's commerce and trade.

"In 1820, one of the military officers stationed there was a young physician named William Beaumont. In 1810, he began a 2-year apprenticeship to a well-established Vermont physician named Benjamin Chandler and in 1812 passed his state's qualification examination. That same year, Beaumont enlisted with the US Army in search of adventure and clinical experience and served as a surgeon's mate in the War of 1812. After the end of that conflict in 1815, he resigned his post to set up a private practice in Plattsburgh, New York. Five years later, he turned his practice over to a cousin and re-enlisted in the Army, which assigned him to Fort Michilimackinac.

"At this distant frontier outpost, Beaumont began the work that culminated in a remarkable, if not outright revolutionary, book - Experiments and Observations on the Gastric Juice and the Physiology of Digestion. But he hardly accomplished this gargantuan task alone. Indeed, Beaumont had the help and the body of a French Canadian fur trapper named Alexis St. Martin.

"The story of Beaumont and St. Martin has been recounted so often it has acquired the finely burnished patina of hagiography. Yet even when stripped of its most sensational layers, their collaboration remains an inspiring and cautionary tale about the boundaries between physician and patient and medical investigator and human participant.

"On the morning of June 6, 1822, as the annual pelt swapping jamboree was underway, a 20-year-old St. Martin waited in line at the American Fur Company's store to make some trades. What began as a rudimentary exercise in capitalism

erupted into a medical emergency when a shotgun accidentally discharged. As one eyewitness described, 'the muzzle was not over three feet from [St. Martin] - I think not more than two. The wadding entered, as well as pieces of his clothing; his shirt took fire; he fell, as we supposed, dead.'

"The gun's contents entered just under St. Martin's left breast, fractured several ribs, lacerated his diaphragm, and left a gaping hole through which portions of the lung and stomach protruded. Beaumont quickly arrived and administered first aid amid the stunning sights and smells of St. Martin's breakfast leaking from the wound. Thanks to Beaumont's quick-witted and precise ministrations, St. Martin did survive the event, albeit with a fistula leading directly into his stomach that remained patent until his last day of life. It was a medical intervention that would soon change medicine.

"For much of the next few years, Beaumont provided daily care and attention to his fascinating patient. Although the wound partially healed, St. Martin remained weak and miserable and refused any attempts by Beaumont to somehow suture the hole shut. As a result of his critical injuries and lengthy rehabilitation, St. Martin was also penniless.

"Medical historians and ethicists have long argued over Beaumont's motives in caring for St. Martin. Alas, the historical record obscures more than clarifies the physician's thinking and intent, as does the striking passage of time, custom, and class, not to mention vast changes in the social understandings of the rights of patients and the obligations of physicians. Assessing the motives and ethical impulses of those long dead is a difficult task for even the most adept historians. Clearly, Beaumont and St. Martin's was a complex relationship consisting of more than sympathy and science. It also included ambition and careerism on Beaumont's part; dependence and need from the ailing St. Martin; and a huge reserve of negative and positive human actions, emotions, and feelings that occupied both men in the years to come.

"On May 30, 1823, for example, Beaumont first recorded his inkling that major scientific observations in this case were possible after introducing a cathartic via a glass funnel into St. Martin's fistula and stomach. 'I gave a cathartic, administered, it is presumed, as never medicine was administered to man since the creation of the world.' The next day, however, Beaumont described taking a destitute and sickly St. Martin into his own home 'from mere motives of charity, and a disposition to save his life or at least to make him more comfortable.'

"Others, however, have pointed out that a local woman named Mary LaFleur first boarded St. Martin through the spring of 1823, and it was not until after Beaumont discovered the ease with which food and medications could be inserted into St. Martin's stomach for further study that he eagerly welcomed the trapper into his home.

"On August 1, 1825, St. Martin finally felt well enough to allow Beaumont to formally begin the studies that served as the basis of his soon-to-be famous book. As Beaumont gleefully recorded, at '12 o'clock [noon], I introduced through the perforation, into the stomach, the following articles of diet, suspended by a silk string, and fastened at proper distances, so as to pass in without pain-viz. A piece of high seasoned a la mode beef; a piece of raw, salted, fat pork, a piece of raw, salted, lean beef; a piece of boiled, salted beef; a piece of stale bread; and a bunch of raw, sliced cabbage [italics Beaumont's]' (p. 125). During this and subsequent experiments, Beaumont also withdrew copious amounts of gastric fluids and chyme for analysis and elaboration.

"Beaumont employed St. Martin as an aide and servant in his subsequent military medical posts and continued to care for him at his own expense. By the summer of 1825, however, St. Martin grew tired of being a human guinea pig and abruptly fled to Canada. It was not until 1829 that physician and patient were reunited after St. Martin made a heroic canoe trip extending from northern Canada to Fort Crawford in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, where Beaumont was stationed. A second series of experiments briefly transpired until a homesick and tired St. Martin returned to Canada. Many pleas and years later, the two met again in Plattsburgh and Washington between 1832 and 1833 for a final round of studies.

"When Beaumont published his treatise in 1833, there was great debate among the medical community about the precise mechanisms of digestion. Similarly, the lay public on both sides of the Atlantic were obsessed with every episode of dyspepsia, flatulence, and heartburn they experienced, resulting in a huge demand for panaceas from their physicians. Many medical experts advocated their own theory of how humans digested their meals, but until Beaumont encountered the ailing St. Martin, no one had first-hand access to a living, secreting stomach.

"Although sales were slow initially, Experiments and Observations eventually generated great excitement in Europe. By 1850, Beaumont enjoyed the status of being the first US-born medical scientist to achieve international renown. No less an authority than Claude Bernard, the Parisian physiologist whose work led to the concept of homeostasis, credited Beaumont with initiating 'a new era in the study of this important organ and those associated with it.' Across Europe and beyond, physiologists looked for individuals with similar fistulas or created them, experimentally, in animals as they labored to elucidate the digestive process. Ironically, like so many prophets in their own land, in the United States Beaumont's theories were initially met with indifference by a medical profession less enthralled with scientific method than their peers in Britain, France, and Germany. By the mid-19th century, however, even his countrymen reconsidered and initiated a cult of hero worship that remains intact to the present day.

"After the publication of Experiments and Observations, Beaumont hoped to conduct another round of experiments, but St. Martin refused all such requests. The constant poking and insertion of food, drinks, medications, tubes, and thermometers into his fistula was hardly enjoyable, let alone comfortable. Moreover, he missed his family and life in Canada and had experienced the ravages of alcoholism.

"St. Martin's refusal to cooperate must have frustrated Beaumont; undoubtedly, Beaumont's relentless coercion and pleading irritated St. Martin. At various points in their collaboration, St. Martin demanded a formal contract. In return for allowing experiments to be conducted exclusively by Beaumont, St. Martin received financial compensation, medical care, and a modicum of respect and attention to his wishes and comfort. Yet even after refusing additional experiments with Beaumont in 1833, St. Martin steadfastly rebuffed the requests of other scientists eager to employ him in search of some additional data. In 1856, 3 years after Beaumont's death, the financially strapped St. Martin finally did consent to participate in a short-lived traveling exhibition show with a quack physician named G. T. Bunting.

"After St. Martin died on June 20, 1880, his family kept the body from being buried or embalmed for 4 days. The corpse decomposed so badly that the odiferous coffin could not even be brought into the church. He was interred on June 24, in a grave 8 feet deep and covered with 2 feet of stones and another 6 feet of dirt to prevent medically inspired grave robbers from exhuming his body for further inquiry.

"Apparently, St. Martin meant what he said when he told his faithful and persistent healer William Beaumont that enough was enough. Unlike the soil placed over his grave, however, neither refusal nor death could cover the stunning contributions he had already made to the medical literature and, more broadly, medical history. Both St. Martin's wound and his willingness to work with Beaumont literally opened the path for a field of study that continues to benefit humankind to the present day" (Markel).

"The most important presentation copy extant of Beaumont's work is the copy Beaumont inscribed to his longtime friend James W. Kingsbury, an army officer whom Beaumont had met when both men were stationed in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin in the early 1830s. Kingsbury was a man of some prominence in St. Louis, where he had married a local heiress, Julia Antoinette Cabanne, and acquired from his father-in-law a 425-acre tract of land that is now home to Kingsbury Place, one of St. Louis's most elegant residential communities. In 1835 Beaumont moved his family to St. Louis, where he remained the rest of his life; his decision to settle in the city, although motivated by professional ambition, certainly also owed something to the presence of his friend Kingsbury there.

"Kingsbury was quite familiar with Beaumont's researches on digestion, as Beaumont had continued his experiments with Alexis St. Martin during his tenure at Prairie du Chien. When Beaumont decided to publish his Experiments and Observations by subscription, Kingsbury, who by then was back to St. Louis, acted as one of Beaumont's agents, distributing prospectuses for the book to local booksellers and other likely purchasers. The Beaumont archives at Washington University's Becker Medical Library includes a letter that Kingsbury wrote to Beaumont on July 14, 1833; this is the earliest letter written to Beaumont to contain a reference to Beaumont's book:

'Your book will be valuable to any one whether a medical man, or a plain farmer, especially when Diet is all the rage as it is now. I hope it may prove as profitable to your purse, as it has to your standing in the great world, where you are located you do not require Alex's intestines to gain you a name or practice. Send me on some 4 or 5 of the prospectus. I shall take one or two copies, my friends will take some & I trust that the talent of the country will have & manifest a feeling for kindred abilities.'

"At the end of his letter Kingsbury repeats his request: 'Send your prospectus as soon as you can we have about 16 doctors here to be examined'" ().

Dibner, Heralds of Science 130; Fulton, pp. 186-190; Garrison-Morton 989; Grolier American 38; Grolier/Horblit 10; Grolier Medicine 61; Heirs of Hippocrates 1141. Markel, 'Experiments and Observations. How William Beaumont and Alexis St. Martin seized the moment of scientific progress,' Journal of the American Medical Association 302 (2009), pp. 804-6.

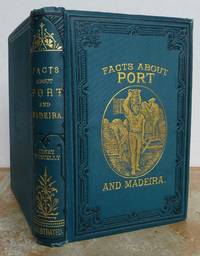

8vo (223 x 140 mm), pp. 280, text illustrations. Original quarter cloth and boards, morocco-backed slipcase (endpapers browned, minor wear to spine and board edges, paper spine label lacking). Custom half morocco slip case with gilt spine lettering.

Reviews

(Log in or Create an Account first!)

Details

- Bookseller

- SOPHIA RARE BOOKS

(DK)

- Bookseller's Inventory #

- 5501

- Title

- Experiments and Observations on the Gastric Juice, and the Physiology of Digestion

- Author

- BEAUMONT, William

- Book Condition

- Used

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Edition

- First edition

- Publisher

- F. P. Allen

- Place of Publication

- Plattsburgh, NY

- Date Published

- 1833

- Keywords

- firsts2022

Terms of Sale

SOPHIA RARE BOOKS

30 day return guarantee, with full refund including shipping costs for up to 30 days after delivery if an item arrives misdescribed or damaged.

About the Seller

SOPHIA RARE BOOKS

About SOPHIA RARE BOOKS

Glossary

Some terminology that may be used in this description includes:

- G

- Good describes the average used and worn book that has all pages or leaves present. Any defects must be noted. (as defined by AB...

- Inscribed

- When a book is described as being inscribed, it indicates that a short note written by the author or a previous owner has been...

- Edges

- The collective of the top, fore and bottom edges of the text block of the book, being that part of the edges of the pages of a...

- Spine

- The outer portion of a book which covers the actual binding. The spine usually faces outward when a book is placed on a shelf....

- Spine Label

- The paper or leather descriptive tag attached to the spine of the book, most commonly providing the title and author of the...

- New

- A new book is a book previously not circulated to a buyer. Although a new book is typically free of any faults or defects, "new"...

- Slip Case

- A protective sleeve, often made of decorative cardboard or leather which houses a book. It is open on one end, so as to allow...

- Morocco

- Morocco is a style of leather book binding that is usually made with goatskin, as it is durable and easy to dye. (see also...

- Gilt

- The decorative application of gold or gold coloring to a portion of a book on the spine, edges of the text block, or an inlay in...

- First Edition

- In book collecting, the first edition is the earliest published form of a book. A book may have more than one first edition in...